Blasphemy in Scotland (From John Fraser and Tom Aikenhead to Raif Badawi)

Garry Otton

John Fraser was a merchant’s apprentice, a bookkeeper who fell foul of the blasphemy statutes of 1661 and 1695 that punished profanity and wickedness at a time when Scotland was in the theocratic grip of magistrates whose religious zealotry was rewarded with incentives by the Scottish Privy Council. They were allowed to keep a share of the fines in return for their co-operation. If they refused, they were fined and replaced by those who could.

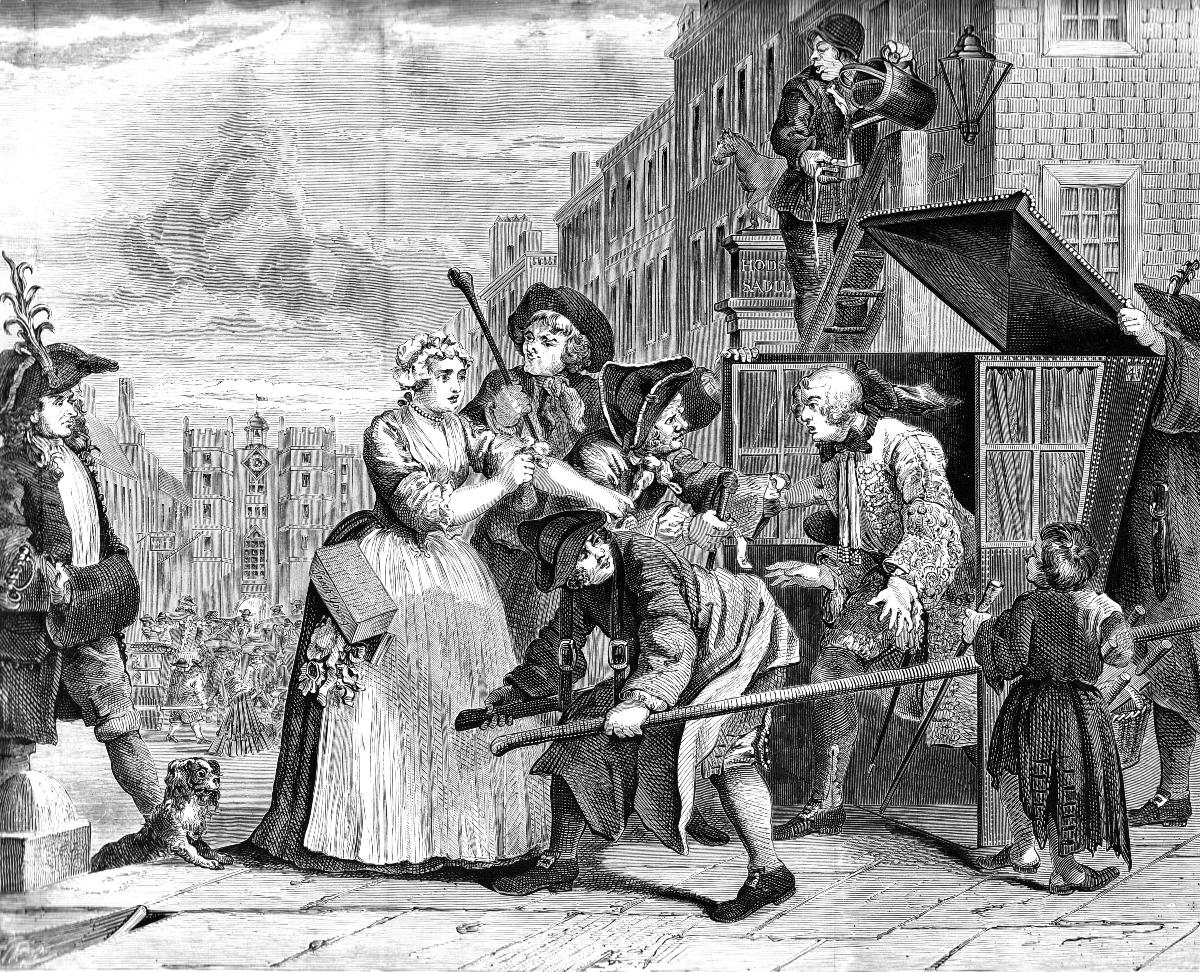

In late seventeenth century England, King William III (‘King Billy’ or William II in Scotland) was busy defending the country from a French invasion and ridding the world of ‘popery’. Scotland was a dark place where Presbyterian ministers burnt witches and hounded young girls to death simply for playing on Sundays. Ministers, elders and deacons ruled over their parishioners with an iron fist ready to banish those unwilling to toe the line with excommunication and all the social and legal ostracism it carried with it. Parishioners guilty of sins like fornication, adultery, slander, assault or breaches of the Sabbath would be made to demonstrate their shame, sitting on a stool of repentance in church amongst the congregation, often in special clothing or wearing a hat emblazoned with words describing their sin.

John Fraser was charged with denying, impugning, arguing and reasoning against the being of God, saying, “there was no God to whom men owed that reverence worship and obedience so much talked off” and claimed established religion was made to “frighten folks and to keep them in order”. When asked what religion he was, Fraser was supposed to have replied that he didn’t have one and was an Atheist. More than enough to have him dragged before the Privy Council.

Fraser argued that he’d been misunderstood. That this was a product of a conversation he had with Robert Henry and his wife, a couple from whom he rented lodgings. Fraser had been reading, as one contemporary put it: “ill books which corrupt and ensnare curious fancies”. A book by Charles Blount was mentioned, but facing a long jail term, he wisely chose to label him a “notorious blasphemer” whilst boosting his Christian credentials with a casual mention of his more normal bedtime reading: Truth of the Christian Religion by Dutch author Hugo Grotius. Fraser, like the author Charles Blount, wasn’t an atheist; simply a critic of religion who saw a different end for the human spirit and argued that the world was older than 6,000 years. Robert Henry and his wife had stormed off after Fraser’s blasphemous utterances leaving him little chance to put things right until breakfast. By that time, Mrs Henry had already reported him to the moral police.

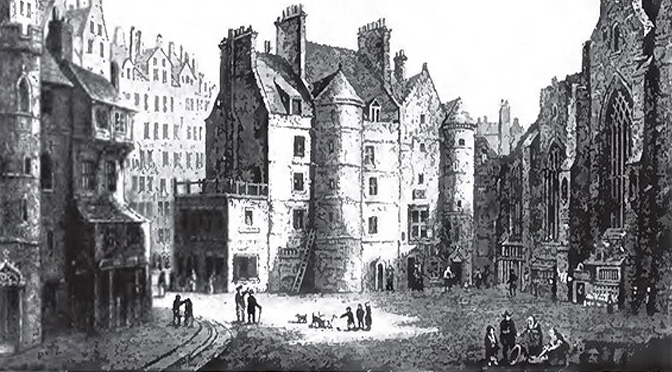

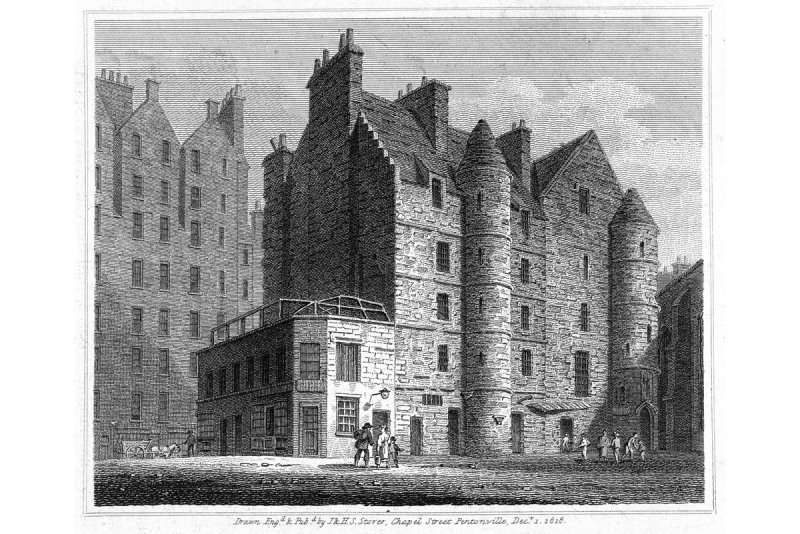

Fraser was locked-up in Edinburgh’s tollbooth in sackcloth. He was still there after they had arrested a young Edinburgh student by the name of Tom Aikenhead and hung him for blasphemy.

While England’s pamphlets, periodicals and booksellers enjoyed more intellectual freedom with the lapsing of their Licensing Act, Scottish Christians clamped down on any influx of forbidden books like Charles Blount’s, Oracles of Reason, Richard Simon’s Critical History of the Old Testament or John Toland’s Christianity Not Mysterious. Toland had lived in Glasgow and been a student in Edinburgh, but his book, lumping Catholic priests with Protestant clergy, earned such notoriety that he had to flee back to his homeland of Ireland. Authors like Thomas Hobbes who argued that only matter existed and Benedict de Spinoza, an atheist who died of inhaling the glass dust he made grinding lenses, were censored in Scotland.

In 1696 the Privy Council found a book reflecting on the Church and State and a couple of pro-Catholic pamphlets in Edinburgh. An edict was issued ordering the search of houses and shops of booksellers for profane literature. Booksellers were ordered to compile lists of every book they sold and hand them over to the Privy Council where zealous evangelical Presbyterians on the committee could run their gimlet eyes down the lists.

It was in this Edinburgh, in 1676, that wee Thomas Aikenhead was born to quarrelsome parents. His father, James, was an apothecary who squandered money and died with large debts. Although Tom’s mother, clergyman’s daughter, Helen Ramsey tried to continue her husband’s business alone, the property was eventually sequestered to pay for her husband’s debts. At a late hour, Helen was beaten and thrown out with her children, including seven-year-old Tom. His mother was sent to the west wing of Edinburgh’s tollbooth for a month as a debtor. Within four days of her release she died. At nine, Tom and his younger sister Anna and 15-year-old sister Katherine were orphans. Sir Patrick Aikenhead, a clerk of Edinburgh’s Commissary Court helped out and, when he was 16, bought a property for Tom on the fourth storey of a tenement house near Netherbow. At this time, Tom became a ‘bajan’ (first year student) at the town college. With classes starting at 6am, he would have been taught to translate Scottish works into Latin before going on to learn Greek and philosophy, theology and medicine. Tom’s regent would have probably been Alexander Cunningham who enjoyed Edinburgh’s taverns “being a young man and having no familie” and was said to be “taken in ane Ba[w]diehouse with any oyr mans wife” for which he was imprisoned in the Canongate.

Young Tom would soon gain access to the college library, and under the watchful eye of a portrait of Calvin, was free to read the books there.

Tom was said to have dismissed scripture as “Ezra’s fables” and “a rapsodie of feigned and ill invented nonsense, patched up partly of poeticall fictions and extravagant chimeras”. He regarded Jesus and Moses as political “impostors” and said he preferred Mohammed. He called Biblical miracles “pranks” and said Jesus and Moses exploited a common training in Egyptian magic to manipulate the vivid imaginations of “ignorant blockish fisher fellows”. The Apostles were dismissed as a company of silly, witless fishermen and he wondered why the world was so long deluded with their contradictions and nonsense.

Such blasphemies saw Aikenhead hauled before the Privy Council on 10th November 1696 where they ordered he be put on trial for his life at the High Court of Justiciary, locking him up in the draughty eastern wing of Edinburgh’s tollbooth, a five-story building already three centuries old where his mother had been imprisoned.

Many of Tom’s classmates testified against him. The gang leader was 21-year-old Mungo Craig who hoped to be a minister and “heard him revile the books of the New Testament and call them the books of the impostor Jesus Christ”; Patrick Midletoune reported “that about the middle of August last, about eight o’clock at night, going by the Tron kirk, he hard him (being cold) say that he wished to be in the place Ezra called hell, to warm himself there” and John Neilson said Aikenhead thought of the contradictory nature of the Trinity as the same as a “squaire triangle”.

Aikenhead’s trial would be before Stewart of Goodtrees, the king’s advocate, Sir Patrick Hume, the king’s solicitor, Hume of Polwarth, the Chancellor and other senior judges. News of Aikenhead’s trial spread. Tom was not so well connected as John Fraser. Unlike many of those who condemned him, he had not invested in the infamous Darien scheme, an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called ‘Caledonia’ on the Isthmus of Panama. Nor could he boast family links to covenanting Christians or any merchant or professional connection of note.

Lord Advocate, Sir James Stewart prosecuted 20-year-old Tom and demanded the death penalty to set an example to others who might otherwise express such opinions in the future. On December 24th 1696, the jury found Aikenhead guilty and he was sentenced to be hanged. Tom petitioned the Privy Council to consider his “deplorable circumstances and tender years”, but to no avail. The Privy Council ruled that they would not grant a reprieve unless the Kirk interceded for him. The Church of Scotland’s General Assembly, sitting in Edinburgh at the time, urged “vigorous execution” to curb “the abounding of impiety and profanity in this land”.

On the 8th January 1697 Tom Aikenhead took the hour-long march to the gallows in Leith after reading a letter saying: “It is a principle innate and co-natural to every man to have an insatiable inclination to the truth and to seek for it as for hid treasure… So I proceeded until the more I thought thereon, the further I was from finding the verity I desired…”

Clutching a Bible, Tom tried to pray with a speech of “great disorder” before a hood was placed over his head and the ‘hempen necktie’ hung round his neck. Michael F Graham delivers the grisly details in his book The Blasphemies of Thomas Aikenhead: Boundaries of Belief on the Eve of the Enlightenment: “Those hanged rarely died instantly, so onlookers probably would have watched him shudder for several minutes as he twisted in the chilly January breeze and gathering darkness, fist clenched, nose and mouth oozing a bloody mucus, gradually suffocating. The moment of death was often marked by the appearance of stains as the victim’s bladder and bowels released their contents”.

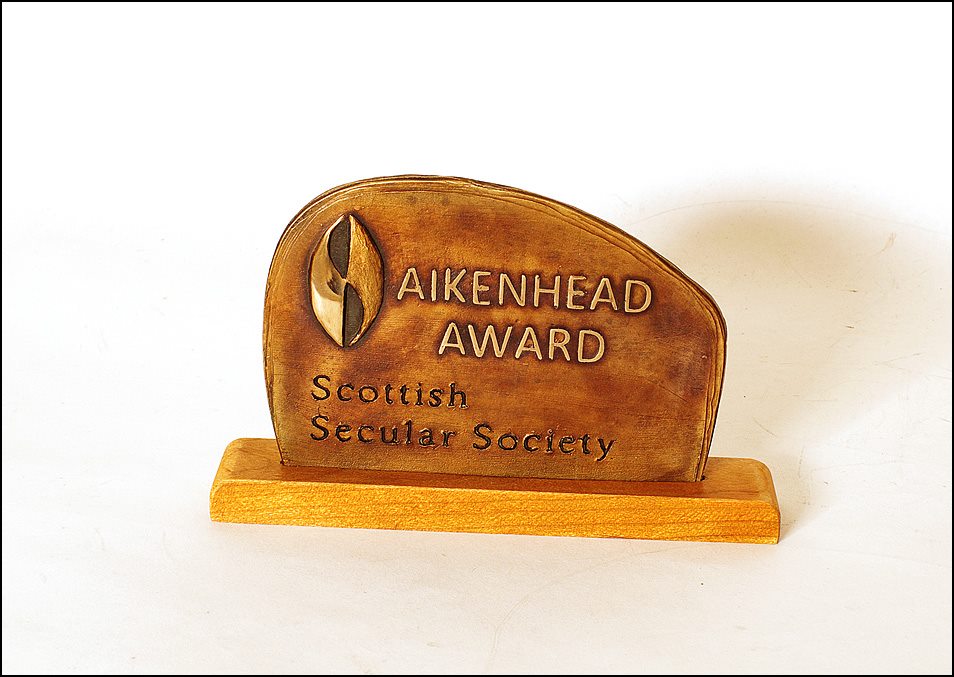

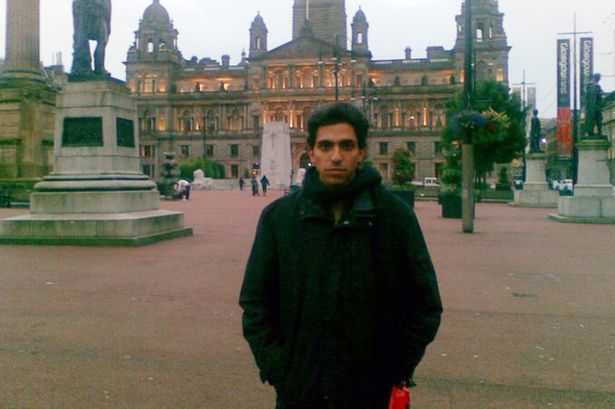

On the 8th January 2015, five days before his 30th birthday, Raif Badawi was awarded the Scottish Secular Society’s inaugural Aikenhead award while he was languishing in prison, convicted under Saudi Arabia’s Anti-Cybercrime Law, “founding a liberal website…, adopting liberal thought” and for “insulting Islam”. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison, 1,000 lashes and a fine of 1million Saudi riyals in Jeddah’s Criminal Court. Badawi’s lawyer, Waleed Abu Al-Khair, a human rights activist, was also arrested and sentenced to 15 years in jail for charges including “undermining the regime and officials”.

Raif received the first 50 lashes on the 9th of January after Friday prayers to the merciful Allah in a square outside a mosque in Jeddah watched by a crowd of several hundred who shouted Allahu Akbar (God is great) and clapped and whistled until after the flogging ended. The hospital advised Raif was too ill to receive the next 50 lashes scheduled for the following week. But in prison he remains.

Garry Otton 2015 (author of ‘Religious Fascism’)