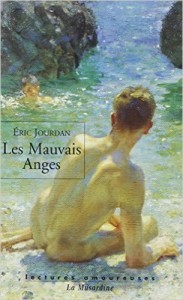

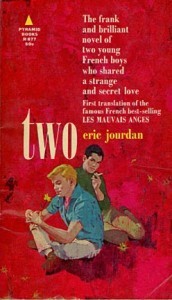

When 16-year-old Éric Jourdan wrote a book about two boys in love, it fell into the hands of the Book Board, led by Catholic priest, Father Pihan. It would be banned for thirty years.

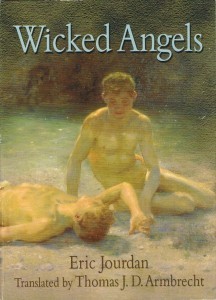

Les Mauvais Anges (Wicked Angels) is a romantic novel involving two Parisian cousins, 16 and 17-year-old Gerard and Pierre, who spend a passionate summer together in Amboise, on the banks of the Loire. The book arcs with the static of teenage rebellion published in the same year as the release of Rebel Without A Cause, starring James Dean. The latest English translation by Professor Thomas J D Armbrecht has a cover by impressionist Henry Scott Tuke who captures the vivid colours of Cornwall in summer as intensely and lyrically as Jourdan writes.

“I brought Gerard’s hand to my mouth and crushed my face into his palm. He spread his fingers and gently squeezed. My lips, which pushed against the hollow of his palm in the middle of the lines of chance and life, wanted to inscribe their kiss there. I got up abruptly. Somehow, we were aware that we had just experienced the most beautiful day of our whole summer.”

Gerard and Pierre’s love is so passionate that almost anything during this hot, sultry summer: the river, grass, trees and sky, shimmer and tremble in sympathy with their erotically-charged romance. “Legs spread, a tuft of pale yellow soapwort against his knees, Gerard slept. His half-opened shirt seemed to be a white wave breaking on the honey-coloured dome of his chest. My eyes followed the muscles of his throat toward the neckline of his collar. Their force seemed to emphasize the contrasting softness of the shadows near his shoulder.” All the same, an emerging darker side resonates against this beautiful backdrop as the author blends pain and beauty on the same palette.

But not everyone was enamoured with the behaviour of Les Mauvais Anges, least of all the head of the 28-member French Book Board, Abbé Jean Pihan, after it was published in 1955. This censorial Catholic abbot wasn’t satisfied with just banning the book; he wanted young Éric – who wrote the book when he was 16 – sentenced for ‘offending public decency’. He was narrowly spared a trial thanks to people like Jean Genet’s lawyer, Pierre Descaves.

Soon after the Second World War, in 1949, a law had been introduced in France responding to a manufactured paranoia over teenage delinquency, aimed at publications destined for youth. It was regulated by a group variously known as The Committee to Survey and Control Published Works Destined for Children and Adolescents, La Commission du Livre or the Book Board. The committee comprised of a cross-party group of clerics, communists and government officials headed by Father Pihan. Homosexuality and subversive material imported from America were first in the queue for regulation as was anything deemed contrary to bonnes moeurs (good morals), licentious or against public order (déréglé).

In Les Mauvais Anges’s first edition, two authors defended Jourdan’s book with appendixes on its artistic qualities. Not that that was ever going to melt the frosty Abbot who feared Jourdan’s artistry was precisely what he was using to detract from what Pihan would have regarded as the deviant and impious nature of the boy’s amorous attractions. Father Pihan (we must suppose) never had sex: he only read about it, and in his opinion, Gerard and Pierre’s love was a sin. Within a year of publication in 1956 until 1985, Les Mauvais Anges was banned.

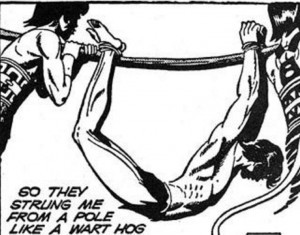

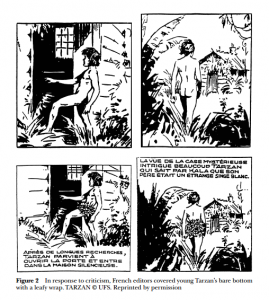

There were plenty of other casualties of the Book Board. Tarzan, a muscular, half-clothed, bestial and poorly educated boy from the jungle was soon a victim and his comics either banned or prudishly re-illustrated. While American imports, Tarzan and Flash Gordon perished in the cartoon cull, Tintin, Lucky Luke and Les Stroumpfs (The Smurfs) triumphed over the censors. The Board put pressure on comic publishers to paint-out the busts of shapely females and cover any scantily-clothed seductresses. Pihan published his own Catholic comic books Coeurs Vaillants and Âmes Vaillantes. (Brave Hearts and Valiant Souls) whilst scorning the transgressive behaviour of female gender roles in other comics, such as a superwoman who fought against men. He deplored the absence of mothers and wives in comics which he regarded as particularly grave for girls.

In 1952, Jean Genet also felt the theocratic stick when he received an eight month custodial sentence for the publication of his novel, Querelle de Brest. The works of the Marquis de Sade miraculously escaped censorship only after the publishers convinced the Board they would not fall into the hands of ordinary people and would be read only by scholars.

With a history of banning views they don’t want heard, religious clerics and fanatics have been central to many of the most prolific incidences of censorship of both fact and fiction, from the imprisonment of Galileo for scientific ideas contrary to Church wisdom to the undermining of the science of evolution in schools. Censorship has hit a wide range of books, from novels like the book published in 1683, Venus in the Cloister or The Nun in her Smock, satirising the constraints of convent life, to Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. In 2015 attacks at the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo saw 12 staff, including the editor Stéphane Charbonnier, massacred by two gun-toting Islamists screaming “Allahu akbar” (“God is great”), which led to the new editor promising he would no longer publish cartoons of Mohammed.

Before the French Revolution some 40% of all prisoners were imprisoned in the Bastille for book-related crimes, and in 1697, 20-year-old Edinburgh student Thomas Aikenhead was swung from a scaffold in Leith for criticising Christ at the Kirk’s behest. Last year, Aikenhead award-winner, Raif Badawi, was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and 1,000 lashes for writing a blog critical of Islam. Bloggers in Pakistan are regularly murdered for speaking their mind, and many are languishing in jail having been judged guilty of thought crime. It seems that religion fears both knowledge and imagination, and uses the blunt tool of censorship to crudely perform the intellectual lobotomising of entire populations. The tragedy is that still people are being sentenced or murdered for merely sharing their views.

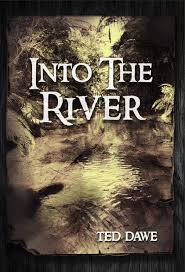

Sadly, even the modern day Western countries are not immune from religious pressure to censor. More recently, in New Zealand, author Ted Dawe told The Guardian how he set out to reach “the dudes who don’t read. Don’t succeed. Appear in the newspapers for the wrong reasons. And, instead of finding their place in society, find it in jails, mental hospitals and morgues”. He set out to give them “one good reading experience that sets them down a new path”. Into the River was a runaway success. Dawe wrote about boys, cars, swearing, girls and fighting. That was until Christian group, Family First, saddling themselves with the “lifting” of moral standards, got hold of it and appealed the decision of the office of the New Zealand censor to licence it. They won. Any selling, displaying or sharing of this award-winning book would be met with a $3,000 fine.

You could imagine Father Pihan bristling at every passage of Les Mauvais Anges; revolutionary for its time, yet revolting in his eyes. The book railed against everything Pihan and his Church stood for: respect for sexual norms, the family, middle-class etiquette, discipline and religious reverence. The story was brutal, contained scenes of torture, rape, unashamedly celebrated juvenile delinquency and included a suicide, a crime in France at the time.

“Screw homework,” declares Pierre. “I’m against what they’re trying to make me learn, anyway. Youth should mean freedom. They’re trying to get us to live our whole lives in captivity, until our skin becomes the colour of the paper of our books. I won’t do it! I won’t!”

The boys demonstrated a lack of respect for their family and institutions that stood in the way of their love, including the church: “Sunday morning was quiet. Large clouds brought shade and a western breeze. I went to church on Sundays to listen to the music, without thinking about anything else. Gerard didn’t believe in anything and stayed in bed.” Pierre didn’t stop long; accidently kicking over a chair on his way out of the church in a symbolic gesture of youthful defiance against the ecclesiastical establishment.

Also to be quashed were notions of romance in young girls and women. In the late fifties, the Book Board lobbied government to extend its powers to cover the romantic novels of the presse du coeur industry. They felt teenage girls were being ‘duped’ by seemingly inoffensive stories leading them into desiring fabulous and luxurious lives well above their social station. The Board thought such romantic novels created ‘troubled feelings’ and ‘tortuous envy’ in young ladies, leading them to be ‘emotionally confused’. Worse, they fretted they might excite sexual desires and amorous longings at an age when there should be none! In these actions of censorship, the motivation of the censor is revealed. Any thought of rebellion, of questioning, of striving for something new, foreign (for that read ‘American’), or more than you have is labelled dangerous and subversive. The Book Board used censorship to keep the French safe from the dangers of thought from outside its realm.

Les Mauvais Anges deals with homosexuality in an almost poetic style. It is Romeo and Romeo; where the boys flaunt their good looks, celebrate their delinquency and cock-a-snoot at the petty bourgeoisie.

As a boy, Éric Jourdan was thrown out of at least ten schools for ‘insolence’ or ‘indecent sexuality’ and lived a Bohemian lifestyle before being formally adopted by American author and Académie française chair Julian Green. Green was born of a sexually-repressed mother, tortured by a Puritanical upbringing and subjected to a Calvinist education, a torture which resonates in his books that wrestle with religion and hypocrisy. Never freeing himself of religion’s cultural grasp, Green later converted to Catholicism. If Julian Green’s writing on sex was subsequently restrained, Éric Jourdan’s work is by contrast fiery and unapologetic. He went on to write more novels and plays, many under different pseudonyms. Charity, Revolt, and Blood was a trilogy he wrote at night in just 29 days.

An elusive man who avoided publicity and refused to mix in literary circles, Éric Jourdan died in February this year at the age of 77. With a Mass for him in the church of Saint Roch in Paris, he was buried next to his adoptive father, in the chapel of the Virgin of the Church of St. Egid of Klagenfurt in Austria.

Garry Otton 2015