The National Secular Society (NSS) is 150 years old this year. It is fitting that it is awarded the 2016 Aikenhead Award for services to secularism. The award is named after Edinburgh student Tom Aikenhead who was hung for blasphemy outside Edinburgh at the behest of the Church of Scotland on 8th January 1697.

The National Secular Society’s birth is as much a result of challenging the privileges bestowed on Christianity as it is on the enquiring minds of the brave freethinkers who played a part in its establishment. Garry Otton takes a look back.

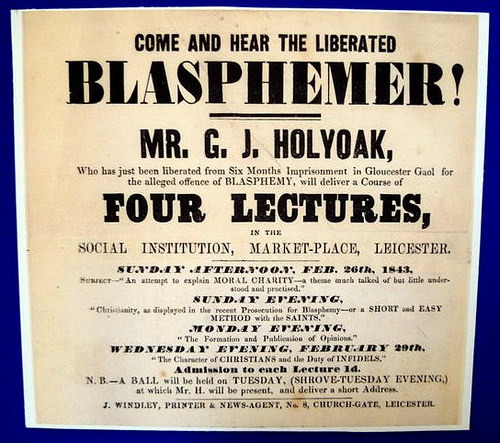

The term secularism was attributed to George Holyoake in 1851 who, like many freethinkers at the time, were Owenists; followers of the social reformer Robert Owen who treated workers fairly at his mills in New Lanark.

Holyoake was inspired by men like Richard Carlile who supported the abolition of monarchy, secular education, the emancipation of women and spent nine years in prison for his troubles. Carlile published The Lion which campaigned against child labour, argued that “equality between the sexes” should be the objective of all reformers and in 1826 published Every Woman’s Book advocating birth control and the sexual emancipation of women. Carlile was prosecuted for blasphemy, blasphemous libel and sedition for publishing Tom Paine’s Common Sense, The Rights of Man and the Age of Reason (which criticised the Bible and the Church of England). In October 1819 Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol with a fine of £1,500. When he refused to pay the fine, his premises in Fleet Street were raided by police and his stock was confiscated. While he was in jail he continued to write articles for his paper The Republican which was now published by his wife Jane. Thanks to the publicity it even outsold pro-government newspapers like The Times.

As well as being an Owenite lecturer at Glasgow University, George Holyoake edited atheist magazine The Oracle of Reason when its first 27-year-old editor Charles Southwell was sent to prison for a year for blasphemy. Like so many of the magazine’s editors, Holyoake also ended up in jail for blasphemy and saying God should be put on half pay. From his Central Secular Society in London Holyoake laid down a secularist doctrine that declared science as the true guide of man; that morality was secular and not religious in origin and that reason was the only authority. His doctrine declared support for freedom of thought and speech and, owing to the ‘uncertainty of survival’, advised directing efforts to this life only. By adopting Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism and French philosopher of Science Auguste Comte’s Positivism he tried to replace the cohesive function of traditional religion with secularism as a ‘religion of humanity’. And so, a new working-class movement was born.

Unsurprisingly, there were no shortage of Christian zealots who would oppose such impudence from secularists of any ilk. The Rev. Brewin Grant made it his personal mission to defeat secularism frequently engaging George Holyoake in head-to-head debates. Another of Rev. Grant’s debating opponents was a more confrontational 25-year-old man called Charles Bradlaugh.

While Holyoake later formed the British Secular Union in 1877, his conservatism, love of secular psalms, prayers, hymns, ritual and desire for religious appeasement proved less popular and clashed with a more direct approach from secularists like Charles Bradlaugh who thought religion was a retarding influence on human life and society and saw ‘freethought’’ as an alternative. As a young man, Bradlaugh had clashed with his parents over his atheistic views and went on to clash with established churches throughout the whole of his adult life.

Risking their livelihoods, Secularists were regularly assaulted. After Bradlaugh tried to deliver a debate on the merits or otherwise of the Bible in Devonport, brandishing the Riot Act, the local mayor went along with the military and a baying crowd of Christians from the Young Men’s Association to break it up. The judge, Sir Edward Parry described it perfectly well in his book, My Own Way (1885): “Bradlaugh walks quietly towards the Gate, steps into a little boat, rows out to a barge moored a little distance from the shore and there nine feet without Devonport Jurisdiction, delivers his lecture: ‘Pocket your Riot Act, friend Mayor: Right About, hence to Barracks, ye Military. Home, home, and gnash your teeth in seemly privacy ye Young Christian Men.’

This is not, it seems a man to be easily persecuted, to be trampled underfoot, or to be whiffed off the face of the Earth by plugshot volleys of dull Bigotry”

Before the National Secular Society was formed, Charles Bradlaugh co-edited The National Reformer and wrote under the pseudonym ‘Iconoclast’. The paper openly supported birth control, a controversial issue at the time.

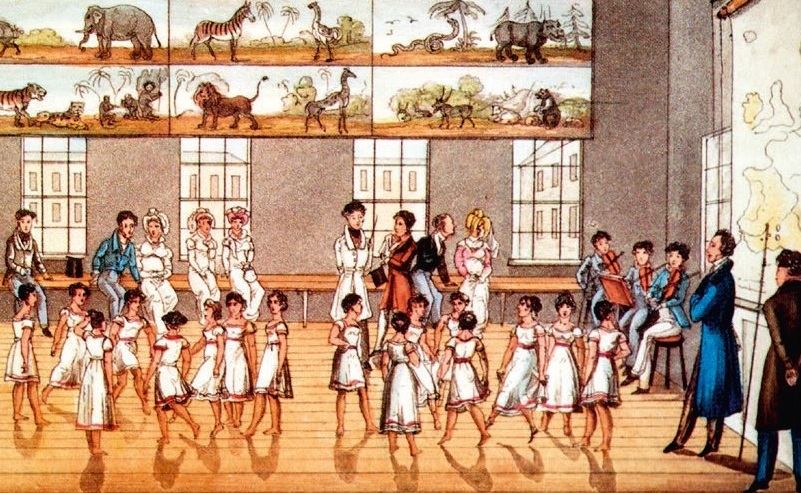

Secularism was booming: Eclectic societies, Zetetic Societies, Rational societies, Owenite societies as well as Secular societies mushroomed across the nation. In Scotland there was a Secular society in Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Perth, Paisley, Greenock, Hawick, Motherwell and Glasgow, which was attended by Keir Hardie’s parents. Glasgow even had its own secular Sunday School.

The National Secular Society was formed by Charles Bradlaugh in 1866 to promote human happiness; fight religion as an obstruction; encourage parliamentary action to remove disabilities; establish secular schools and instruction classes; offer mutual help and fund the distressed and attack legal barriers to Freethought. There were some early victories for the NSS with the removal of newspaper duties or ‘taxes on knowledge’ and the repeal of the Security Law which was aimed at proprietors of periodicals, forcing them to provide financial security against blasphemy prosecutions.

In 1871 a protest organised in Trafalgar Square against grants to the royal family was forbidden. Bradlaugh warned the Home Secretary serving under Gladstone that the threat of force would be resisted. The Government caved-in half-an-hour before the start of the protest.

In reality, Christian privilege was too deeply entrenched in the establishment and constitution for secularists to make any substantial progress.

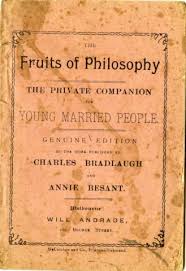

After Mrs Annie Besant had won legal separation from her husband, a minister of religion, she devoted her time to distributing pamphlets and gave talks in support of secularism. Her views prevented her winning custody of her child and at one meeting she was stoned (in a way more attributed to traditional Christian practice). At another meeting, Charles Bradlaugh had to speak against the noise of windows being smashed and bottles being broken. In the same year, in 1873, much to Holyoake’s disapproval, Bradlaugh and Besant published the American, Charles Knowlton’s pamphlet, advocating birth control. The two were arrested, tried and sentenced to six months’ jail sentences before their conviction was quashed. Championing birth control, their The Fruits of Philosophy was a bestseller.

Another renowned secularist from the Isle of Arran who worked as assistant editor at the Edinburgh Evening News by the name of J. M. Robertson heard Bradlaugh speak and was inspired to join the NSS.

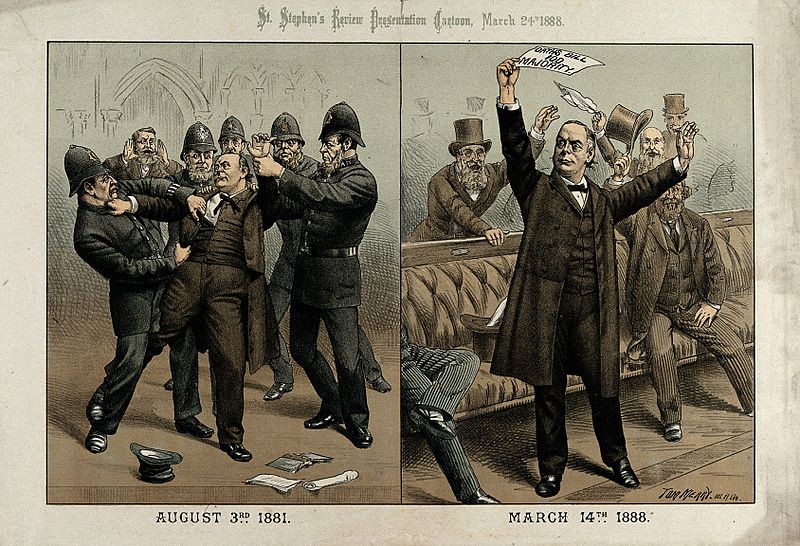

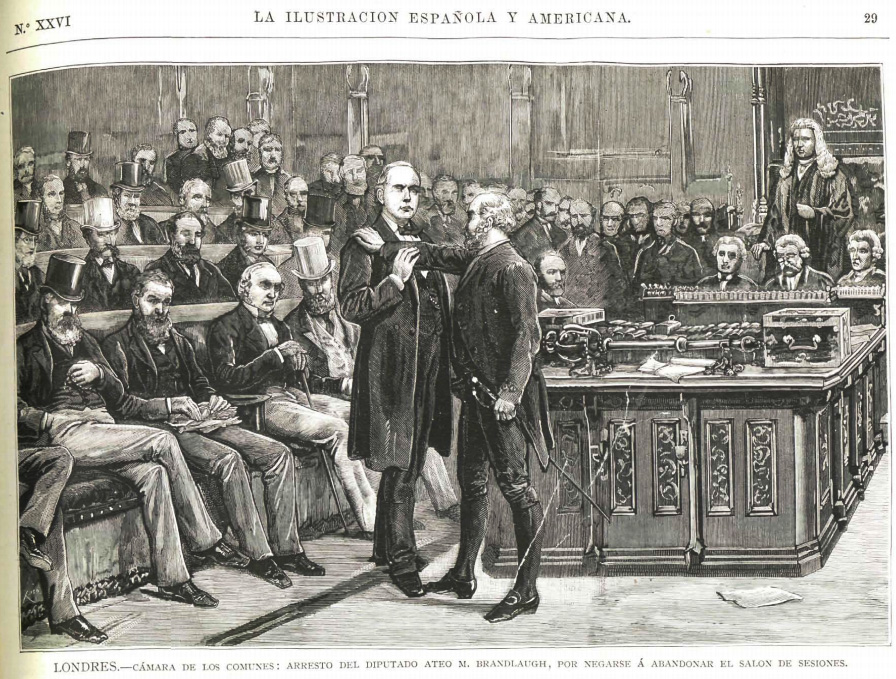

By 1880, secular funerals were legalised and Bradlaugh was elected as an MP for Northampton but was unable to take his seat in the Commons after his request to affirm rather than take a Christian oath was refused. His subsequent offer to take the oath was also snubbed. Bradlaugh was physically beaten, locked in the Clock Tower under Big Ben, prosecuted for blasphemy, sedition and consistently refused his seat in Parliament despite winning repeated elections by the people of Northampton to stand as their MP. He was bullied on all sides from sanctimonious members of his own Liberal Party; MPs from the Conservative Party like Lord Randolph Churchill, Charles Newdigate Newdegate, Lord Chancellor, Hardinge Gifford; the Archbishop of Canterbury and other leading figures in the Church of England and Catholic Church. Bradlaugh was an advocate of trade unions, republicanism, Irish Home rule, women’s suffrage and birth control and years ahead of his time.

Following Bradlaugh’s death in 1891, George W. Foote served as President of the NSS. Foote had also spent a year locked up in Newgate Prison for blasphemy after publishing French cartoons mocking religion in The Freethinker. On receiving his sentence from Mr Justice North (a devout Catholic), Foote famously told the Judge, “My Lord, I thank you; it is worthy of your creed.” Prisoner of Blasphemy, 1886.

After Foote’s death, Chapman Cohen became the new President and the The Freethinker’s new editor in 1915.

1917 saw one of the most important religious legal cases in England: Bowman vs Secular Society. It established that blasphemous libel existed only in scurrilous or profane attacks on Christianity, not in temperate or reasoned criticism and a denial of the truth of Christianity did not render a person or organisation unable to claim the benefit and protection of civil law. It began in 1908 when Charles Bowman died. His will bequeathed a portion of his estate to the Secular Society Ltd. Bowman’s next of kin disputed the validity of the gift to the Society, arguing that the objects of the Society were unlawful insofar as they constituted a blasphemous libel and therefore the gift was contrary to public policy and invalid.

It is clear that the efforts of secularists were clearing the way for the sort of climate that would permit Prof. Sir A. Keith, in his presidential address in 1927 to the British Association to attack the Christian doctrine of Special Creation and defend evolution.

The NSS still faced many challenges from religious bigotry. In 1932 at Birkenhead a lecture hall hired by the society was cancelled at short notice under religious pressure, a subsequent court case ruled against the secularists. In Durham, students demonstrated against the NSS while the police attempted to stop further secularist meetings. In parliament in 1936, Ernest Thurtle MP unsuccessfully made an attempt to introduce a bill to repeal the law of blasphemy, campaigned for Sunday cinemas and against the new restrictive Sunday Trading Act. Two years later in 1938, the NSS held an Annual Conference in Glasgow and was given a civic reception by the Lord Provost and Corporation of Glasgow.

Of course, the BBC’s Chairman Lord Reith’s strict Presbyterian religious convictions were never going to win any friends at the NSS. In 1955, the Home Service broadcast talks by Margaret Knight, a lecturer in Psychology at the University of Aberdeen where she argued that scientific humanism, founded on atheism, would be better for children than Christian teaching. Christian managers at the BBC, working under the assumption that the Corporation had a leading role in evangelising Britain, were aghast. The broadcasts prompted outrage and resulted in Knight being hounded and pilloried by both press and public. The former labelled her ‘Unholy Mrs Knight’ when she appeared on TV in 1957 flanked by three Christian representatives. The NSS acted as a focus for complaints against the BBC’s excessive religious output at a time when the society was busy protesting against the exemption of vicarages, presbyteries and manses from having to pay rates.

After the Second World War there was a cultural war between Christianity and the Establishment on one side, and on the other, a growing demand for change from the nation’s youth.

In its 1966 centenary brochure, playwright Harold Pinter wrote: “The fact remains that children are still indoctrinated in schools at public expense, the Blasphemy Laws are still on the Statute Book, and many humane and rational reforms remain opposed…The work of the National Secular Society remains highly important”.

In 1961, the NSS organised a protest against religious pressure which led to a ban on advertisements for the Family Planning Association on London’s Underground.

David Tribe and Barbara Smoker were notable presidents before the NSS elected Terry Sanderson as its new President in 2006. Sanderson joined the dots between a group now most persecuted by religion and the role the NSS could play in taming religious excess. Sanderson was a popular contributor in Gay Times writing a monthly MediaWatch column. His acerbic style, ridiculing the expressed homophobia and sexual conservatism in the U.K’s media ignited the passions of post Gay Lib activists.

As President of the NSS, Terry Sanderson wrote: “I would like us to position ourselves as a purely secularist organisation with a focused objective, that will not only champion human rights above religious demands, but will also accept that religion has a place in society for those who want it, but on terms of equality, not privilege”. With his Scottish partner, Keith Porteous Wood, the pair brought a new dynamism to the NSS.

It was long after the Gay News blasphemy trial in 1977, led by zealous moral campaigner Mrs Mary Whitehouse, that the Government finally caved-in to NSS demands for the repeal of the blasphemy laws in 2008.

In 1996 Keith Porteous Wood was appointed General Secretary, later Executive Director and took the campaign for secularism to the European Union. In 2007 he received the Distinguished Service to Humanism Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union for his work in building up the NSS and campaigning for secularism both nationally and internationally.

With the growth of the Scottish Secular Society before the Scottish referendum for independence in 2014, the NSS continued to work to promote secularism in Scotland with its Scottish spokesman, now NSS Vice-chair, Alistair McBay.

The NSS continued its efforts to remove the religious privileges still entrenched in the constitution, law and education clearing the way for secularism to gain a new political and moral significance. With successive governments pushing for an increased role for religious groups – despite diminishing numbers of religious believers and the rise in religious fundamentalism in a multi-cultural, multi-faith society – secular values became more relevant than ever. It was against repeated catcalls of ‘aggressive secularism’, that the NSS continued to insist: “Secularism is the best chance we have to create a society in which people of all religions or none can live together fairly and peacefully.”

In the light of recent events like the Charlie Hebdo massacre, who could disagree?

“I crave for every man, whatever be his creed, that his freedom of conscience be held sacred. I ask for every man, whatever be his belief, that he shall not suffer, in civil matters, for his faith or his want of faith. I demand for every man, whatever be his opinions, that he shall be able to speak out with honest frankness the results of honest thought, without forfeiting his rights as citizen, without destroying his social position, and without troubling his domestic peace…”

Annie Besant, ‘Civil and Religious Liberty’ (1882)

Garry Otton, 2016

Further reading: –