Garry Otton

Independent MSP Ash Regan looked suitably pious addressing the audience of around 25 Christians on her plans to legislate against men who pay for sex: “I believe in the power of prayer,” she said, before asking the audience to pray for her.

On 4th November 2025 Ms Regan – or should we call her Ash because we’re in St George’s Tron Church of Scotland in Glasgow and everyone’s being friendly – was garnering cross-party support to get her Prostitution (Offences and Support) (Scotland) member’s bill through the Scottish parliament. It would see men convicted of buying sex hit with up to £10,000 fines and facing up to six-months imprisonment. She said she didn’t want to see men ordering women like pizzas.

Representatives from some of the more militant Scottish Churches were gathered to discuss the so-called ‘Nordic model’ of policing sex. There was Stuart Weir head of Christian Action, Reform & Education (CARE), a group that supports dangerous ‘conversion therapy,’ of LGBT+ people. Chris Ringland for the Evangelical Alliance, another organisation defending ‘conversion therapy’ and Karen Miller from Restore Glasgow that warns on its website “you can’t tackle human trafficking without prayer,” before adding enthusiastically, “three months after we started praying regularly for rescue, women trafficked into prostitution were rescued from the streets around the church where we were praying!”

The cross-party group (CPG) looking into this at Holyrood might’ve been cross-party, but it was certainly not representative of all opinions. The Holyrood group supporting her bill to outlaw buying sex was backed by the Religious Sisters of Charity, an organisation that ran the notorious Magdalene laundries in Ireland. As a punishment for having sex out of marriage, up to 11,000 ‘unsuitable women’ were locked away to do menial unpaid work in 10 Catholic institutions to pay for their keep. One of them was the Religious Sisters of Charity which had been operating since 1922. They were exposed in 1993 when the bodies of 155 women were dug up in their backyard. The Religious Sisters of Charity, along with three other ‘charities’, refused to offer compensation to their victims.

Others sitting on the committee were Labour’s Rhoda Grant who took interns offered by extreme Christian group CARE. And they could be ruthless. An intern for an MSP from the Evangelical Alliance admitted to binning letters from constituents and said in 2015, “I was glad I was the one opening the letter because I was able to bin the letter without actually showing it to the MSPs… Eventually when I left I just shredded them because I thought: I don’t want people to see this as being the way we did business as Christians.”

Also on the group was the SNP’s Ruth Maguire who was called to resign in 2019 as convenor of Holyrood’s Equalities and Human Rights committee after it was revealed in an exchange between her and Ash Regan on Twitter that Maguire had responded to a tweet praising the First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s “positive feminist analysis of trans rights,” with a “FFS,” adding Sturgeon was out of step with the SNP group.

Others on the committee was Labour’s Katy Clark and independent MSP, and Baptist, John Mason who was booted out of the SNP for posting on X: “If Israel wanted to commit genocide, they would have killed ten times as many.” And lastly, Conservative MSP, Jeremy Balfour, a former Baptist minister and lobbyist for the Evangelical Alliance. Scotland on Sunday quoted him saying: “I suspect the only advantage we have (over other people) is that Christians are slightly better informed than the bulk of society and have a better understanding of how politics works.”

Ash told us she had travelled to Sweden to meet Swedish police detective Simon Häggström who enforced Sweden’s ‘Nordic model.’ This was when she helped Rhoda Grant get a similar bill through parliament, but it didn’t receive enough support. Now she was back to try again.

How Ash was going to get sufficient support from the SNP government wasn’t explained beyond hinting she already had half of them in her pocket. I doubt it. After leaving the SNP because of disagreements over what she dismissed as “another matter” is worthy of note. Along with MP Joanna Cherry she challenged reforms affecting the lives of trans people that had won cross-party support after some eight years of debates and consultations which would have brought Scotland in line with many other European countries. Her actions contributed to the UK Supreme Court ruling to overturn Scottish government legislation.

Organizations for the rights of sex workers, such as the Global Network of Sex Work Projects, as well as global human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, do not support the ‘Nordic model.’ It has been implemented in Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Canada, Northern Ireland, France, Ireland, Israel and one state in the U.S. (Maine.) Since implementation, violent crimes against sex workers in Ireland have almost doubled. Only seven men have been convicted in 15 years and there has been no decrease in demand for sex workers. In 2016, National Ugly Mugs, a service which allows sex workers to confidentially report incidents of abuse and crime, showed that reports of abuse and crime against sex workers greatly increased after Ireland’s adoption of the ‘Nordic model’ approach by criminalising the purchase of sexual services. The figures stated that crimes against prostitutes increased by 90%, with violent crime increasing by 92%.

In the face of changing patterns in male sexual behaviours and many platforms where men and women meet for sex without paying, debates about the ‘Nordic model’s’ success or failure still proliferate.

The meeting was opened by Stuart Weir from CARE who, for reasons best known to himself, asked us to cast our minds back 2000 years to a woman Jesus saw needing a man without an ulterior motive. She was apparently thrilled to be touched by Jesus because it was the only safe male that had ever touched her. Having hugged and kissed a good number of sex workers and dancers without ulterior motive, I trust my position in Heaven is now secure.

The meeting was a bit slow getting down to business and started with a warning from Stuart of the disturbing nature of the film we were about to watch. We were advised that we were welcome to retreat to a quiet corner if it all became too much. The video opened with a misspelling: Prositution and the voices of sex workers describing the appalling treatment they received from men, including a woman that tried to end her life at 11. Rude words like ‘watersports’ and ‘cum-in-mouth’ were displayed as part of ads used by Direct Escort Glasgow. An internet search for them only brought me a list of fake pictures of sex workers from Japan and Asia advertising on VivaStreet. What was most disturbing was the lecherous voices of men using the sex workers. “I don’t give a fuck if you’re not 18,” sneered one. But it was a voice that sounded identical to Christian militant and UKiP member Richard Lucas that nearly had me scurrying to a corner of the room with a vial of smelling salts!

Next up was Karen. Representing Restore Glasgow, it turned out she was an interpreter for Albanian migrants. She explained the ‘Lover Boy Method,’ which involved blackmailing women into sex work before trafficking them into Scotland. Cases of PTSD amongst women escaping these nightmares were highlighted. In England, victims had 30 days to enjoy a safe space; in Scotland it was 90 days. Karen stressed “They are voiceless.” In the face of this legislation, many sex workers would agree. This was countered by Pastor Emma who cornered me at the end. She told me she only ever heard the voices of sex workers promoting the trade in the media. I asked her why someone from an organisation like ScotPep wasn’t invited. I was told that other churches were invited but they hadn’t accepted the offer. Probably too busy doing Christian things like handing out food to the homeless, I thought.

Ash was confident she would get her bill through Parliament and praised the ‘Nordic model’ success in Sweden and elsewhere. Citing Germany’s partial decriminalisation, she advised the market had exploded with an increase in trafficking and sex workers being paid less.

She felt legislation that allowed police to arrest ‘kerb crawlers’ was “going very well indeed” and explained her battle was against a “lobby well-funded by the ‘prostitution trade’.” No mention of over £2.5 million profit the Evangelical Alliance raked in annually or CARE’s £2 million. And no mention was made of the notorious Religious Sisters of Charity on the CPG.

She declared the evidence of men buying sex was in front of us all, citing a 15-story tower block with a different fetish on every level. I’ve not found that, but she might have been referring to the 7-storey Pascha brothel in Cologne which has an interesting history. She finished by saying she didn’t want to see the arrests of men, but only a ‘societal change.’

Leslie Thomson, Chair of Secular Scotland said: “The selling of sex is not even a crime in Scots Law. The actual crime is Soliciting for Prostitution, which falls under the Public Places (Soliciting) Act 2007, both the buyer and the seller can be prosecuted.

“And strangely enough, sex workers organisations and charities, including ScotPep, fully support the decriminalisation of Soliciting. The law as it stands immediately makes criminals of sex workers who solicit publicly. Therefore, the same sex workers are all the more likely to solicit by other means, effectively putting them ‘underground’ which puts them in a far greater place of danger. And of course, because the buyers also fear being prosecuted, they too will use these underground sources, which means the more dangerous among them go undetected, and represent a much greater danger to sex workers.

“And you’ll notice I have continually used the term ‘sex workers’ here. Ash Regan says that her Bill prioritises, “the safety, dignity and rights of women and girls.” While the vast majority of sex workers are indeed female, such a statement completely ignores the fact that there are also gay and transgender sex workers.

“In all the years that Ash Regan has been MSP for Edinburgh Eastern, the ward I live in, I have never once before heard her come out with anything overtly religious. I do not believe one word of her sanctimonious reference to believing in “the power of prayer”. This appears to be nothing short of opportunism to rally the support of the religious right.

“That Ash Regan is ambitious cannot be denied. Upon the resignation of Nicola Sturgeon as SNP Leader and First Minister, Regan stood for the leadership of the SNP, only to come third behind Humza Yousaf and Kate Forbes. At that time, she defected from the SNP to the Alba Party, making her their sole MSP. After the death of Alba Party leader Alex Salmond, Ash Regan stood for the leadership of the party, but was defeated by party favourite, Kenny MacAskill. She then quit from the Alba Party to stand as an independent MSP, which she claims was to focus better on her prostitution Bill, which she believes she would have a better chance passing outwith the Alba Party.

“I do not wish to cast shade upon anyone’s personal life, but for the representatives of the religious right, condemning the practises of sex workers (one of whom Jesus allegedly protected), to welcome and support Ash Regan, a divorced woman, seems to be more than a tad hypocritical to me.”

According to a report published by Dr Niina Vuolajärvi from the London School of Economics, “the ‘Nordic model’ of sex trade legislation purports to target sex buyers and third parties, ostensibly removing sex sellers from criminalisation. However, this approach leaves sex sellers, in particular migrant workers, ever more vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

“This is exacerbated by broad third-party legislation, where all assistance in the sale of sex is prohibited. Under these laws, for example, landlords and hotel owners can be accused of pimping, which has led to a dire lack of housing and safe spaces for sex workers. Those who took part in the research reported difficulties in accessing health and legal services, and even in opening bank accounts.”

I care about the treatment of women. But I also defend their rights of women to run their lives how they see fit. It is economic deprivation that challenges women, not sex work. And make no mistake, we’ve been here before.

Scaremongering by Christians has a precedent. The consequences of sex in Victorian and Edwardian Britain resulted in the spread of sexual diseases and unwanted pregnancies. In turn, these sparked a wave of Christian zeal and the foundation of such organisations as the Association for Moral and Social Hygiene, the National Purity League, the Public Morality Council and the National Vigilance Association. William Coote, the founder of the NVA believed his organisation to be in an “energetic legal crusade against vice in its hydra-headed form,” declaring in his book ‘A Romance in Philanthropy,’ published in 1916, that it was a “hand-to-hand fight with the world, flesh, and the devil.”

People were terrified of sexual diseases like gonorrhoea and syphilis. And for good reason: There was no cure. It’s why so many men conformed to Christian edicts and refrained from sex until after marriage while some would deliberately seek sex with virgins or even children.

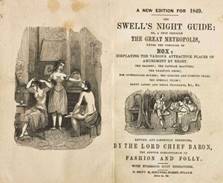

Prostitution and abuse of young girls in and out of brothels was rife in Victorian Britain. More wealthy Victorian men boasted their own magazines: ‘Sporting’ guides which were little more than shopping catalogues of available females. These detailed sex workers’ ages, physical descriptions, personality type, and their cost, usually £2 – £3 or £5 for a virgin. It has been estimated that there were more brothels than schools with an estimated 80,000 sex workers in London.

‘Swell’s Night Guide,’ offered “a peep through the great metropolis… with numerous spicy engravings.” The book rated individual women, describing one, Miss Allen, as a “perfect English beauty” and another, Mrs. Smith as a “very agreeable woman” with “pouting lips.”

Christians attempted to rehabilitate ‘fallen women’ with the establishment of reformatories. But living in a reformatory was worse than jail. Christians often considered women were pursuing sex work because of their own selfish desires rather than admitting it was the highest paid work women could do. Women were forced to stay in the reformatory for a minimum of two years until they were ‘cured.’ During that time, they needed to seek forgiveness from God for their sins of the flesh and repent to qualify for a roof over their head. They were woken at 5am, made to pray four times a day, attend regular Christian services, perform hard labour and be locked in their rooms by 8pm.

Christian groups like the NVA and feminists – who were normally Christian in Victorian times – found a common goal in fighting prostitution. Not until 1876 did the Freethought Publishing Company produce a pamphlet on contraception, but they were prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act. Secularist Annie Besant, who bravely represented herself in court became the first woman to publicly endorse the use of birth control, arguing for its potential to alleviate poverty.

In his sensational exposure in ‘Pall Mall’ magazine, Journalist, W.T. Stead published ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,’ proving how easy it was to purchase the virginity of a 13-year-old girl. For a mere £5, Stead purchased someone’s daughter, whom he called ‘Lily.’ This covered the cost of a medical examination to ensure that she was a virgin, and a cut to the brothel owner. The money the girl earned was taken by Lily’s parents who were alcoholics. After confirming that Lily was a virgin, the medical examiner recommended that Stead drug the child with chloroform so she would be unconscious and not put up a struggle while he raped her. The public was so horrified when they read Stead’s articles that it led to the raising of the age of consent from 13-years-old to 16 with the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885 to protect women and girls. It was introduced into Parliament by MP Henry Labouchère who, at the last minute also lodged an amendment to protect young boys from the act of ‘gross indecency,’ but because there was no age of consent for homosexuals, for the following century, men of all ages would be prosecuted for consensual sex in private, providing new grist for the Christian mills. Churches were vociferous in preventing gay emancipation but didn’t enjoy the support of feminists until today when many play an active role in joining the churches in denying a small percentage of trans men and women their rights.

W.T. Stead was seen as a hero for fighting for the rights of women and was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. He died on the Titanic in 1912 aged 63. Today, the Stead Memorial Fund continues to fight against sex trafficking.

Efforts to legislate and control women’s sexual passions were often clumsily administered by an elderly and inexperienced judiciary or religious leaders. But generations of young people remain determined to define their sexual behaviour outside of politics, courts and religious institutions.

Policing sexuality was not always considered entirely appropriate for an all-male police force, so, during the First World War, Women’s Patrols were paid by the police authorities to shine their torches into the faces of soldiers and police the “foolish, giddy and irresponsible conduct” of girls. Patrolling the streets, parks and open spaces, they ‘saved’ drunken soldiers from “women of evil reputation” by administering black coffee laced with bicarbonate of soda, which usually made them violently sick.

One patrol was so outraged by the sight of a “heaped mass of arms and legs and much stocking” on one of the benches along a towpath, she had the seats boarded up!

Garry Otton 2025.