Lord Reith (centre)

Packed with 26 unelected clerics and assorted toffs, on 25 July 1990 in the House of Lords, Earl Ferrers defended the BBC and helped seal the fate of Britain’s last remaining offshore free radio station: Radio Caroline. He put the case for the new Broadcasting Act that would make it legal for government agents to board broadcasting ships in international waters. That would be able to act with legal impunity, taking someone’s life if necessary to silence anyone who dared broadcast to Britain in the same way the BBC World Service had been doing for years. Ferrers was the same noble Lord who, during the debates over an equal age of consent, considered the age of consent for gay men should be 75. The State Broadcaster itself was first led by a Christian fascist, Lord Reith, who not only publicly approved of Hitler’s actions but who railed against the establishment of commercial broadcaster, ITV with the words: “Somebody introduced Christianity into England and somebody introduced smallpox, bubonic plague and the Black Death. Somebody is minded now to introduce sponsored broadcasting … Need we be ashamed of moral values, or of intellectual and ethical objectives? It is these that are here and now at stake.”

Lord Annan stood up to protest. He thought the Government’s measures were “high handed and bullying,” adding, “Section 7a empowers Servants of the Crown to seize property and detain persons, to require the crew to produce documents and – this is most extraordinary and reprehensible – to grant officials immunity who are engaged in search and seizure! There must be some question as to whether it is necessary to extend the powers beyond the police and customs officers. That could mean anyone at all!

“The immunity clause is iniquitous. What if a member of the crew resists and is knocked overboard into the water and drowns? His family will have no case in damages; there will be no case of manslaughter brought against the officer who did this. It is a licence for official thuggery!

“I have a feeling that the Government will regret passing a measure of this kind. They are trying to bring down a mosquito with artillery fire. I know also that they are trying to bring Radio Caroline down by illegal means. My purpose is to bring home to the Government and to the public that the Government are about to pass a clause which is illegal in international law and an affront to those who care about the principles of justice.”

Like the age of consent amendment to the Criminal Justice Bill, the debate took place late in the evening. A vote was called, the doors were opened, and a large number of peers poured in from the bars to register their vote for the Government before heading home. The Government won 93 votes to 29.

MARCONI

After the first human voice was transmitted in 1919, the Armed Forces were putting pressure on the Post Office to ban further broadcasts until the Government could think up ways of regulating it.

In the twenties, Marconi’s managing director Godfrey Isaacs became embroiled in what was to become known as the Marconi scandal. A Select Committee had to be set up to investigate the serious allegations of insider dealing between himself, his brother Isaac Rufus (who was then Attorney General), the Postmaster General, Herbert Samuel and the Prime Minister himself, Lloyd George.

Licences were eventually issued by the Government, which allowed stations to broadcast just 15 minutes a week.

In July 1922, one of these new stations broadcast some rather trivial local news of a garden fete. The press was quick to respond, calling it: “unconsidered trifles of the lightest type,” so the Conservative Government resumed responsibility for broadcasting and formed the British Broadcasting Company Limited under the directorship of the rather dour Scotsman, John Reith. Bisexual sculptor Eric Gill was commissioned to work on a statue of Ariel now posing above the doorway of Broadcasting House. Reith, whom it has often been hinted was a closeted homosexual, was so shocked at the size of Ariel’s genitals he demanded they be shrunk. Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Cosmo Lang told Reith: “Whoever holds your job is, or should be, the most influential man in the country.”

In 1926, 16 European countries, including Britain, participated in the first conference on radio in Geneva and carved up the airwaves between them.

RADIO LUXEMBOURG

Before Radio Luxembourg, Captain Plugge toured France with the very first car radio manufactured by Philco and beamed music from Radio Normandy to Britain after midnight. ‘Auntie’ – as the State Broadcaster became known – was not amused. Even less so when she heard the French government was behind the 200 kilowatts of dance music pumping out from Luxembourg to England every night. The Postmaster General wrote to the Head of the BBC saying: “We must use all our influence to stop this.” In an internal memo of 7th April 1933 the BBC suggested persuading leading newspapers not to refer to it. It went on to say: “It seems to me that a possible way of combating Luxembourg would be to allot the wavelength to somebody else, not as their only wavelength, but to get someone with a sporting spirit to take it on and try and clear the channel.”

The British Government monitored Radio Luxembourg from its listening post at Tatsfield, compiled a list of foreign stations they claimed might be experiencing interference, and demanded Luxembourg accepted a frequency more befitting the size of the country. Luxembourg, of course, refused. The Government then successfully persuaded the Newspaper Publishers’ Association to completely censor any information or programme content connected with Radio Luxembourg.

By now, any artist who worked for Radio Luxembourg could expect to be blacked by the BBC. Its own announcers still spoke in punctilious statements between records and women had to address the microphone in ball gowns.

During the Second World War, the occupying German fascists used Radio Luxembourg as a propaganda station. In 1944 a special American task force under the directions of the Psychological Warfare Division liberated the station and silenced Lord Haw-Haw’s (alias William Joyce’s) infamous voice. He was later hanged for treason.

During the fifties, the 500 or so new records released each week in Britain could only be aired on the BBC Light Programme’s ‘Mid-day Spin’, Sunday’s ‘Family Favourites’ or the daily ‘Housewives’ Choice.’

In 1960, Macmillan’s Conservative Government set up the Pilkington Committee to discuss local radio of which they found “no evidence of public demand.” However they did recommend a trial, but the Government resisted in its White Paper of July 1962 saying that they “would prefer to take cognisance of public reactions before reaching a decision.” A bit odd considering the last time the public had heard local radio was before the Home Service was set up at the outset of the Second World War.

THE ‘PIRATE’ STATIONS

The very first European offshore free radio station – one of a handful, off Scandinavia – was Radio Mercur, broadcasting off Denmark in 1958. The Scandinavian Governments put their heads together to bring in their own anti-’pirate’ legislation on August 1st 1962. Sweden’s Radio Syd, however, continued, resulting in the imprisonment of the station’s owner, Ms Britt Wadner.

The Scandinavians benefited by the arrival of Radio Scotland whose broadcasts reached them from off the coast at Dunbar on 242 metres from the MV Comet on New Year’s Eve 1965 before it sailed round the coast to broadcast off Troon. Newspaper recruitment ads for Radio Scotland read: “Why not be a disc-jockey and join the glamour set!” DJ Jack McLaughlin, fresh out of university, said: “I used to wear a wee bunnet and queen it about!”

By Easter 1964 channel tracking stations watched as several new radio stations set themselves up around the British coast. One of them was Radio Caroline carrying popular DJs like Kenny Everitt and Tony Blackburn. Then Postmaster General Reginald Bevins, declared that Radio Caroline was causing interference to a Belgian station concerned with communications to ships at sea and was interfering with British Maritime Services. A former BBC radio engineer reported back in the Daily Mail that Radio Caroline was broadcasting nowhere near the maritime wavelengths.

The Post Office cut off the ship-to-shore service permitting its use for maritime emergency use only. They then set about warning the general public that they would be liable for prosecution under the Wireless Telegraphy Act of 1949 if they so much as listened to the free radio stations.

British Customs and Excise Officials sent out the MV Venturous in an attempt to board Radio Caroline to see her bonded stores. After it was pointed out to them that the ship was in international waters they steamed away. HM Customs and Excise ruled that passports had to be carried by all persons on board tenders going out to the ships. HM Waterguard, HM Immigration, Special Branch, CID, Board of Trade, Ministry of Transport, British Railways, the Port of Health Authority, Trinity House and the Local Harbour Board continued to make regular inspections and Caroline House in Chesterfield Gardens was forbidden an entry in the GPO telephone directory.

It was reported that less than 1% didn’t support the stations. The Daily Telegraph reported “Radio Caroline has a bigger afternoon audience in the areas that it covers than all the BBC programmes put together.” The Labour Government was determined to ignore public opinion, but with such a slim majority they couldn’t risk taking any action at this stage. Conservative backbenchers, however, were making maximum capital out of the situation with many openly supporting the free radio stations.

The sudden introduction of the Continental Shelf Act in September 1964 extended our territorial waters to include the continental shelf and put paid to stations like Radio Sutch and Radio 390 broadcasting from old sea forts. Ships would not be affected by this act since they were afloat and outside the three-mile limit. Talk of moving one of the stations to the last remaining sea fort outside the three-mile limit was thwarted at the last minute. The Government blew it up.

21-year old Jean Ollis appeared in a series of BBC advertisements that read: “People like me like the BBC Third Programme,” (the forerunner of Radio Three). After payment she was happy to announce that she in fact listened to Radio Caroline.

Radio Caroline attempted to put its case backed by a team of independent radio experts but was unable to gain any time on BBC radio or television to do so. Phonographic Performance Limited and the Musicians’ Union refused to enter into discussions with them. Radio Caroline was particularly eager to point out that prior to its broadcasts just four companies owned 100% of record sales. The free radio stations had been successful in whittling that down to 80% in just three years. All the leading stations continued to pay money to the Performing Rights Society and were regularly bombarded by performers and promoters eager to have their material broadcast.

In 1967, after just three years of opening, the National Opinion Polls announced Radio Caroline had the greatest weekly audience of any commercial station in the world.

The Labour Government under Harold Wilson did its best to avoid free radio becoming an election issue until they had a bigger majority in the House. That opportunity came in 1966. Postmaster General, the late Tony Benn, prepared the case against free radio. He argued that they stole wavelengths; paid no copyright on the records played; were a hazard to shipping as they interfered with ship-to-shore communication; flouted international regulations and gave the country a bad name abroad. The Government went on to cite 12 European countries – all signatories of the Strasbourg Treaty – registering complaints of interference with their own authorised broadcasts.

At one minute past midnight on 15th August 1967 the Marine Offences etc. Bill became an Act of Parliament and one by one the offshore free radio stations closed down.

THE DUTCH ‘PIRATES’

After the Marine Offences Act, young listeners were left to the mercy of BBC ‘Wonderful’ Radio One. Records were selected by a panel of five producers headed by a woman in her fifties and by the end of 1973; Edward Heath’s Conservative Government was establishing local commercial radio stations licensed by the Independent Broadcasting Authority, (IBA). The Prime Minister appointed the Director General, and the 11 Government Appointees were selected from a Civil Service list. The IBA stations pressed ahead with their expansion across the country imposing themselves upon the listening public in varying degrees of awfulness.

By 1970, Radio Veronica had a new neighbour on the North Sea: Radio North Sea International. On FM, Medium Wave and Short Wave bands, RNI – like the BBC World Service – could be heard world-wide from its transmitters on the MV Mebo II, anchored in international waters. The British Government ordered jamming of the transmissions, something no western nation had ever done since the war.

In 1973, Billboard’s top selling pop newspaper, Record Mirror was stunned by the results of their survey which saw BBC Radio One collect less than 5% of votes for best radio station! Radio North Sea International, Radio Caroline and even the Dutch services of Radio Veronica and Nordzee Internationaal were voted better in the poll.

European Governments abiding by the terms of the Strasbourg Treaty put heavy pressure on the Netherlands to close the stations which happened at midnight on August 31st, 1974 when Minister Harry van Doorn successfully introduced legislation to close the stations. All but one ship stayed at sea to broadcast. Whilst Radio Caroline broadcast album music in the evening, another entrepreneur, Sylvan Tack, the manufacturer of ‘Suzy’ waffles in Belgium, broadcast the Dutch language programmes of Radio Mi Amigo from the MV Mi Amigo, 18 miles from the English coast.

Radio Mi Amigo broke a virtual American monopoly on imported music to Britain. One of the first Euro-disco hits to be plugged on Radio Mi Amigo was Patrick Hernandez’s ‘Born To Be Alive’ and the gay discos did the rest.

In 1975 the Belgium police carried out raids on the offices of Radio Mi Amigo but Sylvan Tack had moved all the operations to Playa de Aro in Spain, a country not yet a signatory of the Strasbourg Convention. The British Government assisted the Belgians by making frequent raids on any boat tendering the MV Mi Amigo from Britain. Of those tenders making the journey from Spain, two police launches, a naval patrol boat and a helicopter escorted them. The fishing boat anchored half a mile from the ship was staffed by British Government officials and photographers.

Whilst the Government was monitoring Radio Caroline’s English service and Radio Mi Amigo’s Dutch service broadcasting from the same ship, more sinister developments took place on land. On January 11th 1979 the police and a Home Office official raided the home of Derek McCauney, a medical student, without a search warrant. A model boat bearing the name ‘Mi Amigo’ was found and McCauney was arrested and charged with advertising a ‘pirate’ radio station. He had been making a number of these boats to sell at a benefit dance in aid of a hospital for children. At the same time, Southline Printers, who printed the hand-typed Caroline Newsletter for free radio enthusiasts campaigning for a review of Clause 5.3 (f) of the Marine Offences Act, had pressure put on them by representatives from Scotland Yard to stop printing. Michael Brigden and Carolyn Oakley appeared in court facing 24 charges under the Marine Offences Act for offering for sale various souvenirs of Radio Caroline in their magazine. Scotland Yard also visited Geoffrey Baldwin, the founder of the free radio club, the Caroline Movement. He had the facilities of a P O Box address used by the Caroline Movement withdrawn and was also warned that he might face prosecution. In April 1975 free radio supporter Jackson Hunter was convicted after refusing to pay his fine in Liverpool Magistrate’s Court and subsequently imprisoned for 60 days for displaying a Radio Caroline car-sticker. David Hutson was also convicted and fined for selling badges bearing the words: ‘Radio Caroline’.

LASER 558

On January 19th 1984 a new free radio station took up anchor close to Radio Caroline: Laser 558. With American backing Laser 558 began broadcasting from the MV Communicator anchored 14 miles off the Essex coast. Laser 558 enjoyed phenomenal success. With its claimed audience of eight million listeners, mostly in southern England, it was seriously threatening the BBC/IBA duopoly on radio broadcasting whose listeners were deserting them in droves for the brash, new American station.

The American Government was asked for their assistance in identifying the station’s financial backers and Lord Thomson of the IBA accused the Government of “apparently condoning theft” of the airwaves for not acting more firmly against Laser.

Both Vatican Radio and Voice of America are amongst many stations that have not been ‘allocated’ wavelengths. The USA boarded their only free radio station after just four days of broadcasting yet has regularly beamed ‘pirate’ television programmes to Cuba. In Britain, the attempt to broadcast anti-Chinese Government propaganda from the Goddess of Democracy was met with widespread support from MPs and programmes from a ship, broadcasting to the former Yugoslavia, even received financial backing from the EC.

During the course of their programmes North Foreland Radio told the MV Communicator that they were getting interference claiming Laser 558’s transmissions were coming out over their signal on 500 KHz. The crew switched off their transmitter but still the interference persisted. Radio Caroline offered to turn off its transmitter to see if the interference could be traced to them. It could not, and was later traced to BBC Radio One and the World Service.

During the early eighties, a profusion of small, land-based pirate stations were taking to the airwaves. Their popularity was briefly glamorised by Lenny Henry’s portrayal of Delbert Wilkins of the Brixton Broadcasting Corporation. Robert Atkins, Under-secretary of State for Industry remarked rather ominously: “It has been suggested to the BBC that they should consider their position.” New legislation was brought in making it a criminal offence to make an unlicensed broadcast with a prison sentence of up to five years.

The DTI erected notices all around the British coast warning boat owners the penalties of supplying ‘pirate’ radio ships and began an expensive surveillance operation 15 miles off the English coast beside the MV Communicator and MV Ross Revenge. The DTI kept records of any visiting vessels and journalists and passed them on to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

An embarrassing situation occurred one weekend when the DTI vessel gave chase to a boat full of sightseers. A Customs and Excise vessel came out; presumably to watch the ships while the DTI vessel was away. As it prepared to leave, the DTI vessel ordered it to stop. At this point the Customs boat sped off north with the DTI vessel in hot pursuit. “We’re a Customs boat!” they called back on the radiotelephone. Another sightseeing boat had meanwhile come out to see the ships, so the DTI vessel simply turned round and chased that back to Ramsgate instead.

On occasion, it has been alleged the DTI vessels cut across the bows of visiting boats. The DTI counterclaim this with reports of sightseers pelting them with bottles.

The DTI called a conference of handpicked media representatives to explain why they wanted the stations off the air, adding that it was costing the taxpayer around £25,000 a month.

On November 6th 1985, the Government gained a substantial victory and, after a long siege, the MV Communicator, home of Laser 558 was escorted into Harwich.

RADIO CAROLINE

In 1987, Anthony Elliot, editor of London’s Time Out magazine was prosecuted for two offences of publishing times, wavelengths, and contents of Radio Caroline’s broadcasts. Time Out said it saw the prosecution “as another attack on the freedom of the press. The case calls into question the legality of any media examination where such examination includes the report of truthful information about station operations or programmes. Apparently, the Government wishes the public to believe that pirate radio stations do not really exist. So the media must not, on pain of heavy fines, report any evidence to the contrary.”

Howard Beer, a boat owner who was unsure of the legality of organising sightseeing trips to Radio Caroline telephoned the DTI for clarification. He received no satisfactory reply and when he was subsequently arrested, received a nine-month prison sentence. It was overturned after seven weeks in remand by an appeal court ruling the sentence too long.

Quite suddenly, the Government introduced the Territorial Sea Act 1987 extending British territorial waters to a further twelve miles. The incident went virtually unnoticed. It took the unusual course of being passed in the House of Lords before receiving a reading in the House of Commons as it was considered a ‘non-political bill.’ The MV Ross Revenge took up anchor from her previously safe haven in the Knock Deep and moved 14 miles off the English coast off North Foreland.

John Birch of the Caroline Movement claimed his organisation and that of Caroline’s had been subject to phone tapping, saying: “a certain amount of key information had only been discussed on certain telephone lines. This immediately caused Caroline’s Station Manager, Peter Moore to have some checks made and soon established that at least four groups of telephone lines were being tapped.

For several weeks the MV Ross Revenge went under surveillance by the DTI who anchored a mile from the ship at night and flew low-flying light aircraft over the ship to take photographs while a helicopter filmed the ship and crew. Tenders approaching the ship were warned there was a half-mile exclusion zone round her.

At 10.50 on August 18th 1989, John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ and Chris de Burgh’s ‘Lady in Red’ were broadcast indicating an emergency on board.

At 12.22, broadcasts from the Dutch station on 819 kHz abruptly ceased in mid-record unceremoniously ending 30 years of Dutch free radio to Belgium and Holland. Music still continued on Radio Caroline’s frequency on 558 kHz.

Radio Caroline’s one-o’clock news revealed that the Landward, a vessel of the DTI carrying DTI officials and Dutch PTT officials had attempted to board the ship to “discuss its future.” Programmes continued as normal the next day until 12.42 when Chief Engineer Peter Chicago interrupted Caroline Martin’s programme to announce that the Dutch tug Volans had pulled alongside. Later, Caroline’s theme tune by The Fortunes was interrupted by another announcement: “This is Radio Caroline, the radio-ship Ross Revenge, anchored in the international waters of the North Sea. This is a Panamanian vessel being boarded illegally on behalf of the Dutch and British Governments. There’s a Dutch tug alongside, and they are already on board the ship. They have already used violence against certain crew members here on board the Ross Revenge. If you can help us, please call your local radio station, local media, anything – anyone you think can help us. Call, please, now, before Caroline goes!”

Listeners jammed the Dover coastguard with calls whilst records with cryptic messages played: ‘Do You Know What It Is Like To Be Free?’ the Beatles singing ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘Love, Love, Love.’

Whilst the officials from the Dutch PTT were smashing equipment in the generator room, an official came into the studio. A deejay asked: “Would like to say anything, sir, before we go off the air?” At that point, at 13.08, 19 August 1989, the transmitter fell silent.

What might otherwise have been the main news of the day was overshadowed be an even greater tragedy on another boat. A Thames motor vessel owned by Amalgamated Roadstone, a corporation with major government shareholders, the Bow Belle, rammed and sunk the MV Marchionesse whilst hosting a gay party.

Radio Caroline attempted to make a comeback broadcasting at night. A few days later, the DTI paid them a visit. As the spectre of the Landward approached them, the Captain on the Ross Revenge asked them their intention. “Fishing,” they quipped. The Captain then asked them how long they were intending to stay. “Longer that you will be,” they replied.

Radio Caroline went off the air on July 2nd 1990. Its signal distorted by Spectrum Radio, a small incremental station licensed by the Government for the London area. Its test transmissions on Caroline’s frequency of 558 kHz were so powerful listeners as far away as Scotland and the Dutch coast received them. On 1 January 1991 the Broadcasting Act gained royal assent and the free voice of Radio Caroline was finally silenced. Spectrum Radio’s reception settled down to being barely audible north of the Watford Gap outside London.

Bob Geldorf’s film company Planet Pictures began filming a documentary about Radio Caroline for BBC 2’s Arena programme. It was shown on March 1 1990. Three days before its broadcast the legal department of the DTI contacted the producers and warning them that they could be committing an offence. The BBC bowed to pressure and important cuts were made to the footage.

On Wednesday 20 November 1991, Radio Caroline’s ship, the MV Ross Revenge broke her anchor chain in a violent storm and was later towed to Dover harbour after hitting a sandbank.

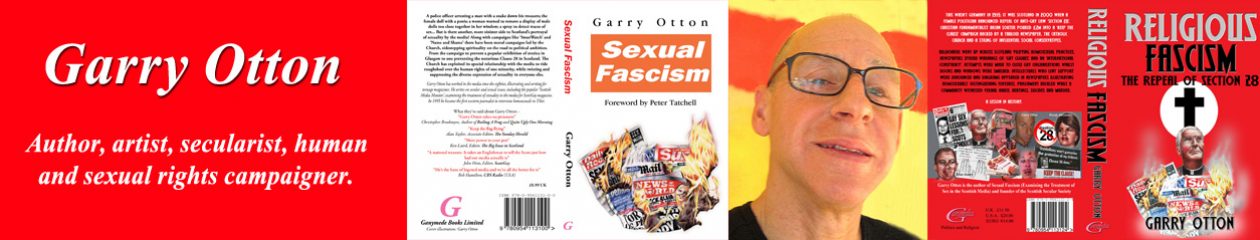

Garry Otton 2014